By Shmully Blesofsky

At 1137 Park Place, a stately brownstone just east of Kingston Avenue, once lived one of Brooklyn’s earliest female trailblazers — Mrs. Ellen C. Donnelly, among the first licensed women undertakers in New York City.

Born in Manhattan in the mid-19th century, Ellen Donnelly entered a world where women were rarely permitted into the funeral trade. But around 1910, after the death of her husband Richard J. Donnelly, she took over his small undertaking business, operating directly from their home on Park Place. For three decades she served the growing neighborhoods of Crown Heights and Bedford-Stuyvesant, preparing the departed and comforting their families with quiet professionalism at a time when few women had such independence.

Her obituary in the Brooklyn Eagle called her a “pioneer mortician” and praised her charitable work. Her funeral was held at St. Gregory’s R.C. Church at Brooklyn Avenue and St. John’s Place, with burial in Calvary Cemetery. Surviving her was her son, Private Richard J. Donnelly, Jr., then serving in the U.S. Army during World War II.

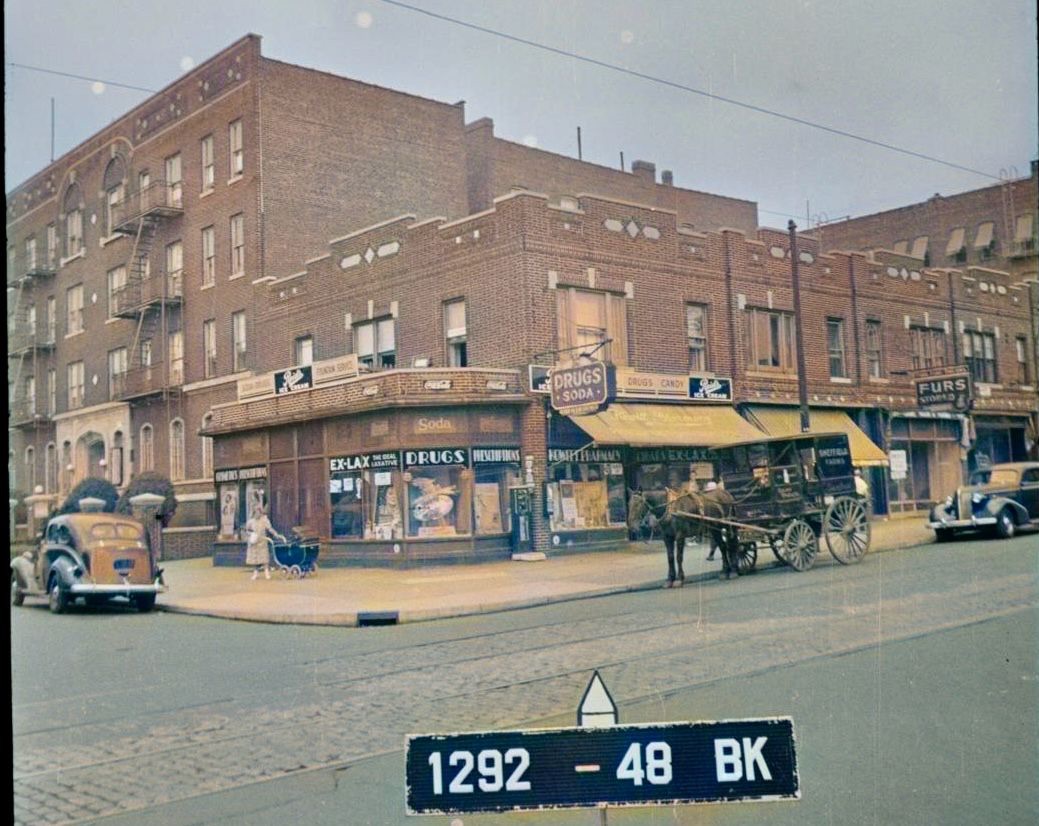

The house itself dates to the turn of the century, built during the burst of residential growth during the height of the St. Mark’s Avenue District which today we know as Crown Heights North. Just two blocks south of St. Mark’s, 1137 Park Place reflects the transition from open farmland to refined urban streetscape – when speculative builders and small contractors filled the newly graded blocks with elegant brownstones and limestone-fronted rowhouses. Their designs favored restrained ornamentation: projecting bays, rusticated bases, and broad stoops catching the afternoon light, hallmarks of Brooklyn’s confident turn-of-the-century architecture.

By the mid-20th century, 1137 Park Place continued to pulse with neighborhood life. Residents included Gertrude Anderson, a Red Cross nurse listed there in 1919; Charles E. Gregory, a World War I veteran and custodian at St. Mary’s Hospital who lived there until his passing in 1952; and Maureen Kelly, who was interviewed by the Brooklyn Eagle in 1949 about how she kept cool during a summer heat wave (“Stay in the bathtub as much as possible,” she advised).

From undertaker to nurse to soldier — this Park Place home quietly mirrored the evolving spirit of Brooklyn itself: industrious, resilient, and full of character.

Today, the house stands proudly restored — listed for just under $3 million — its new kitchen and bathrooms designed in seamless dialogue with the home’s 1890s craftsmanship. From the parlor floor, the original heart of the residence, one feels a striking sense of elevation: the tall windows open above the tree-lined street, offering that timeless Brooklyn view where history and modern life meet. Every molding, banister, and bay window invites you to step not just into a house, but into a living chapter of Crown Heights history.

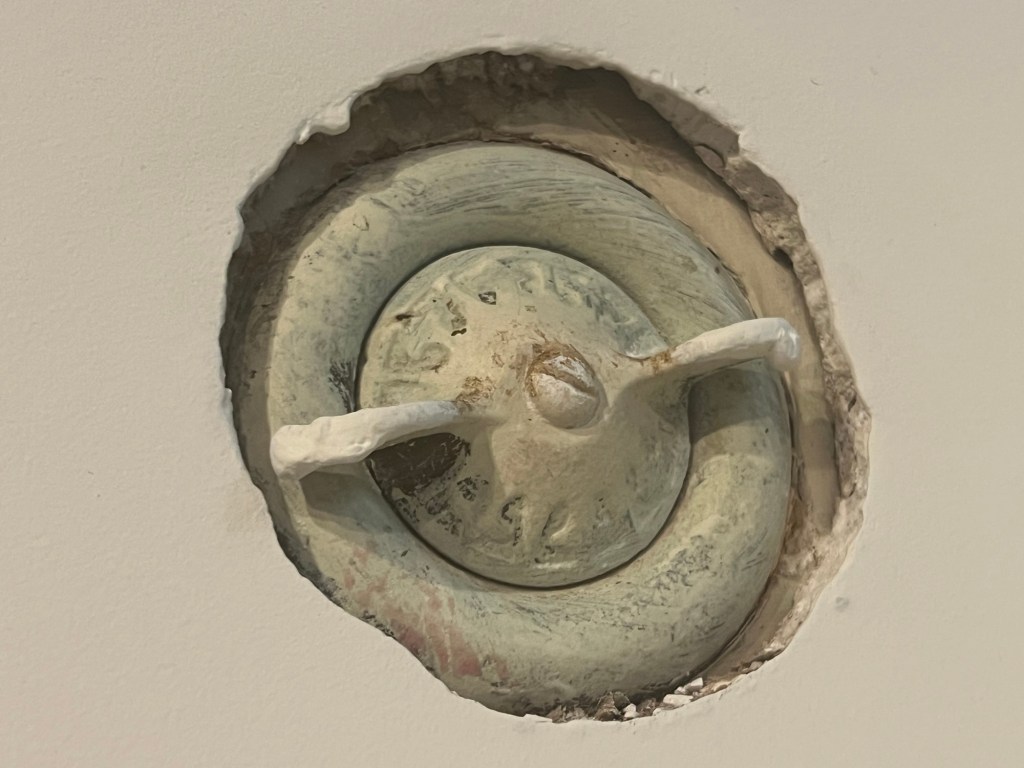

This weathered brass valve, tucked discreetly into the parlor wall, is a small but evocative relic of 19th-century Brooklyn craftsmanship. Likely part of the home’s original gas lighting or radiator system, it dates from an era when builders took pride in even the most utilitarian details. The circular fitting, once polished to a soft gleam, would have controlled either the flow of gas to a sconce or the steam that warmed the limestone rowhouse through long winters. Its worn patina—greenish from oxidation and hand-touched over generations—quietly tells the story of a home built before electricity and central heat, when light flickered from open flames and warmth came hissing up through iron pipes. Today, this humble fixture remains a tactile link to the house’s first residents, a century of stories literally turning on its axis.

This exquisite woodwork detail, likely part of the original 1890s mantel or pier mirror, captures the restrained grandeur of late Victorian design in Crown Heights. Carved in rich oak or walnut, the motif features a stylized acanthus leaf rising from a classical urn — a symbol of rebirth and domestic prosperity popular in the Gilded Age. Each flourish was hand-tooled, not machine-stamped, reflecting the craftsmanship of builders who treated even functional interiors as works of art. The golden inlay, still gleaming against the mellow patina of the wood, hints at the home’s original elegance — when gaslight flickered across polished parquet floors and every carved surface contributed to a sense of refinement. Standing before it today, you can almost imagine the first owners gathered by the hearth, their reflections caught in the tall parlor mirror above, surrounded by the quiet dignity of turn-of-the-century Brooklyn.

Leave a comment